In trying to get to grips with politics in Preston in the 19th-century I thought it would be helpful to examine the parallel careers of the social reformer Joseph Livesey and the town’s MP and Guild Mayor Robert Townley Parker . Livesey has been generally treated as a secular saint, while Townley Parker has been portrayed as an Orange Order bigot and persecutor of Catholics. Neither portrait is a truthful representation of its subject: they were far more complex characters, and tracing their careers in detail is proving very revealing about the true nature of politics in the town through the century.

This website aims to provide a platform for similar articles. All contributions considered.

A detailed survey of Preston was carried out at the end of the 17th century and the surveyors’ sketch plans have been preserved. Internal evidence suggests they were produced in 1685 and they have been loosely attributed to the antiquarian Richard Kuerden. The plans include the name of the owner/occupier of each property.

John Scansfield was suspected of being a Jesuit and an agent of James II when he visited Lancashire and the North in the 1680s. That was certainly how he was viewed in Preston when he appeared in the town in 1688.

Amongst an extensive collection of 17th-century Lancashire maps and plans found at Towneley Hall, including street plans of Lancaster and Preston, were road maps showing routes through the old county from south to north. Supplemented by an itinerary through the county prepared by the antiquarian Richard Kuerden, they provide a wealth of topographical information.

Anglo-Irish relations in mid-nineteenth-century Preston

Jack Hepworth has contributed an article on Anglo-Irish relations in mid-nineteenth-century Preston. It builds on the dissertation that he wrote for his BA degree at Durham University. Jack graduated with a first in history and was awarded a Vice-Chancellor’s Scholarship for Academic Excellence in 2014-2015 and the Gibson Prize for History in 2015. Jack was born and brought up in Preston and South Ribble.Anglo-Irish relations in mid-nineteenth-century Preston

Barley, beer and the Lancaster Canal Barley, beer and the Lancaster Canal

The maltster at the Maudland Maltkilns was John Noble, who was one of the principal opponents of the town’s Conservative MP Robert Townley Parker.John Noble — Preston’s Catholic radical

Col Thomas Bellingham Bellingham/Rawstorne diaries Bellingham/Rawstorne diaries . Editing of Bellingham's diary has now been completed, with the exception of those entries for his two periods in Ireland, which are beyond the scope of this website. Editing of the entries in Rawstorne's diary that overlap with the Bellingham diary has also been completed. The two diaries cover the period from August 1688 to May 1690: including the Glorious Revolution, the accession of William III and the campaign in Ireland.

Cambridge collection -- graduates of the university with a Preston connection

The long list of Preston’s Cambridge alumni would provide a starting point for a Who Was Who for the town … or, to judge by some of the entries, would furnish a rogues’ gallery. Examples from both categories are listed here. All the women who feature in the full list of alumni (or alumnae?) are included.

Some notable Preston Cambridge alumni

'Child murder'

Fr Bernard Page who saw service on the Western Front and in revolutionary Russia. On his return to Preston Fr Page produced a history of a Catholic charity that provides much interesting material on life for Catholics in the town from the early 18th century:When Preston's Catholics had to lie under ye Bushel Fr Tom Baines , who died in France in 1918, and Fr John Myerscough .

Fr Baines and Fr Page

Climate science pioneer's More on John Tyndall's Preston connections

Conflicted sexuality in Edwardian Preston

A rather sad tale of unrequited love gives a rare glimpse into the private lives of the well-to-do families living in the Winckley Square district of Preston at the beginning of the last century, revealing the extent to which homosexuality was viewed as unacceptable at that time.

Counting Catholics

Counting Catholics in 19th-century Preston

de Hoghton property deeds

Notes on hundreds of Preston property deeds stretching in time from the reign of Edward I to that of Elizabeth I.

Desirable Dwellings

Domesday Preston

An attempt at a reconstruction of the Preston landscape shortly after the Norman Conquest.

Edwin Waugh in 1882 .

Edwin Waugh's Portrait of Preston A disturbing view of Victorian Preston — 1

Ellen -- a working-class biography Ellen Moulding's biography

Foster Square: Victorian Preston's 'worst slum'

A 19th-century census enumerator in Preston's Little Ireland was so incensed by the conditions in which the residents in his district were forced to live that he used the cramped space of his census return to express his feelings.

'Frailty! thy name is Lancashire!'

How to explain the continued electoral success of the Conservative party in Lancashire in the second half of the 19th century despite a widening franchise that gave working-class men the vote? The results prompted one Liberal commentator to complain, “Frailty! thy name is Lancashire!” One possible explanation is the superior organisation of the Conservatives at grass roots level when throughout Lancashire and the rest of the country the party’s mobilising force was the now almost forgotten Primrose League. The league recognised that the working-class defiance of earlier in the century had given way to a deference to their betters that could bring the working class into the Tory fold. The focus here is on the league’s operation in Preston (consistently loyal to the Tories from 1865 to 1906) and nationally, but it operated successfully in all corners of the county.Preston and the Primrose League

Frenchwood Tannery

One of the foulest of the many obnoxious trades of Victorian England was the tanning of leather. The Dixon family of Bank Parade, Avenham, developed Preston's largest tannery on their own doorstep.

Friargate's

Fulwood Forest

One of the major influences on the development of Preston in the Middle Ages was the imposition of the Forest of Fulwood by the Norman conquerors.

Gormanston Register

The Preston family, who took their name from the town in which they settled in the 13th century, established themselves in Ireland shortly after, becoming the Viscounts Gormanston. One of those Irish descendants collated the family property deeds at the end of the 14th century, including scores relating to Preston.

Great War conscription

Why did so very few conscripts from Preston's working-class districts find a place in the officer's mess, and what does it say about the class divide in Edwardian Preston?

Harris Library

Some of the material previously held at the Harris has been transferred to Lancashire Archives. It is as yet unclear what remains at the Harris and what is now housed at Bow Lane.

Henry Barnacle

The claim to fame of an astronomer who served as principal of a Preston college at the beginning of the last century was based on a completely false depiction of the part he played in the scientific expedition to Hawaii to measure the Transit of Venus. The true account of his time in what were then known as the Sandwich Islands has been revealed in journals kept by other members of the expedition.Henry Barnacle and the Transit of Venus

Historian Dorothy Marshall - a product of Preston's Park School

One of the 'overlooked' female historians of the last century who, among her many more serious achievements, is credited with getting the future politician Roy Jenkins into Oxford.

Irish ‘ghettoes’

Does the district known as Little Ireland that was firmly established in Preston by the middle of the 19th century qualify as a ‘ghetto’? It was home to Irish immigrants attracted by the town’s employment opportunities and driven by the famine that was devastating their country. The map above suggests there might indeed have been an Irish ghetto in the town, but the reality was more complex.Irish ‘ghettoes’ in 19th-century Preston

Irish not welcome in 1830s Preston Irish not welcome in 1830s Preston

Jacobins in Preston

Edward Baines: youthful revolutionary?

E. P. Thompson, the celebrated historian of the English working class, wrote that the journalist and Whig MP Edward Baines was secretary of a Jacobin Club in Preston at the end of the 18th century.

Jacobins in Walton-le-Dale

Another writer produced a fictional autobiography of a Jacobin born in Walton-le-Dale who accompanied Thomas Paine to Paris at the time of the French Revolution. 20th-century historians treated the fiction as fact.

Kuerden’s Preston

The antiquarian Richard Kuerden left a detailed description of Preston at the end of the 17th century.

Lancashire land measurement

When is an 'acre' not an acre? When it is one of the several variations on the statute measure to be found on Preston documents well into the 19th century.

Lewis Carroll's Lewis Carroll and Preston

Moor Park

Preston's claim to pre-eminence in the provision of public open space was, some years ago, called into question by a leading academic. Was he right?

When Sir James Allan Park, the recorder of Preston, laid the foundation stone of St Peter’s Church (now the University of Central Lancashire Arts Centre) on a summer’s day in 1822 on land donated by his son, also named James Allan, he can hardly have expected the ceremony to have sparked an angry article in the Manchester Guardian in which he was accused of ‘unparalleled humbug’ and his son of property speculation.Piety and profit in 19th-century Preston

Platford Dales -- a medieval town field The history of Platford Dales

Poverty and privilege in Victorian Preston A tale of two Pedders

Preston deeds

A list and abstract of the deeds to the properties Cockersand Abbey held in Preston at the end of the 13th century. They provide glimpses of the life and landscape of the medieval town.

Preston Guardian

Preston historian Henry L. Kirby compiled a four-volume digest of articles in the Preston Guardian covering the period from 1844 to 1905. He has left a valuable chronology of the town's development. See also Anthony Hewitson's Preston chronology 705-1883.

Preston History Library Preston History Library

William III, Col. Thomas Bellingham and James II

Preston, Ireland Their visits, and accounts of their sufferings, were recorded by the diarist Thomas Bellingham .

Preston Moor

Preston Moor was originally a part of Fulwood Forest that was separated from the forest and granted to Preston by a charter of 1252. It continued to play an important part in the economy of the town up until the 19th century.

Preston’s

The pace of development of Preston's landscape from the Middle Ages onwards was marked by slow organic growth until the dynamic and swamping impact of industrial development in the 19th century.

Public School Prestonians

'Why were the newly rich businessmen of the Lancashire mills sending their children south to expensive schools, wondered the Taunton Commission, set up in 1864 to examine the public schools. It was so that "they may lose their northern tongue ... and be quite away from home influences".'

Reforming Preston

When Margaret Spillane (or Ainscough, as she then was) became the first woman to graduate from Trinity College, Cambridge, her success was largely due to the dissertation she wrote on municipal reform in Preston. That was 40 years ago, when, during a summer spent researching at the Harris Library and the Lancashire Record Office, she benefited from the help and advice of the Preston historian Nigel Morgan (see below).

The result of her researches was a masterly treatment of the transformation in the government of the town, changing the corporation from a self-selected body into an elected assembly. However, this did not result in a transfer of power from the Tories to the Liberals and Radicals as in most other boroughs. The drawing of the new ward boundaries effectively guaranteed Tory control of the council.

Reforming Preston

Social and Political

The Preston historian Nigel Morgan's postgraduate thesis on the political history of the town in the early 19th century. An essential source for the period of the town's most dynamic changes.

Septimus Tebay

From the back streets of Preston to the back streets of Farnworth by way of Cambridge and headship of Rivington Grammar School, the life of Septimus Tebay is a remarkable story of clogs to clogs in one generation.Septimus Tebay -- maths prodigy

Stephenson Terrace

The name of the famous Stephenson has for more than 150 years been wrongly attached to this elegant terrace.

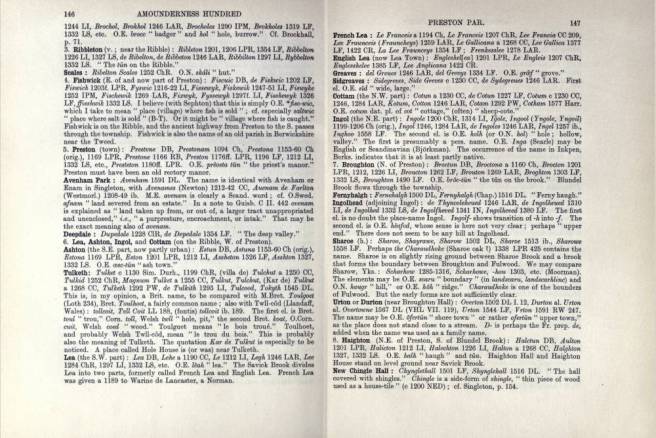

Street name origins

Back in 1992 in faraway New Zealand a professor of botany published The Street Names of Preston to mark the 80th birthday of the author of the book, his Prestonian father, John Bannister.

When Arthur Edward Pedder of Preston got an urgent message from home in 1861 telling him that the family bank had collapsed following the death of his father, he was in India on a Grand Tour that he set off on after leaving Eton. At Eton he was reckoned to be one of wealthiest boys in his year. Yet when he returned to Preston he found he was penniless and had a mother and two sisters to support. He took a job as a bank clerk, and set about rebuilding his fortune.The fall and rise of Arthur Edward Pedder

The contents of the hall were put up for auction -- including Sir Henry's Egyptian mummy.

The many wives of The marriages of the Rev Parr

The Pedders of Preston The Pedders of Preston

The story of

Kim Travis has traced the history of the district from pre-Norman times up to the present day. It is a marvellously detailed reconstruction.

Trade directories

The Preston directories are a rich source for historians, providing the raw materials for mapping the changing social geography of the town from the beginning of the 19th century well into the 20th.

Victorian Preston's

At the end of the nineteenth century a small army of insurance agents was tramping the streets of Britain. They were collecting weekly contributions on the millions of policies taken out by working class savers anxious to protect their dependants from the terrible consequences of the sudden loss of a family breadwinner. The lives of the Preston contingent of that army are examined here.

When Preston's Catholics had to lie under ye Bushel

Who owned Lancashire?

Who owned Lancashire?

Who owned Preston

The contribution of the volunteers working on the tithe schedules project for the Lancashire Place Name Survey (98,200 records and counting) is shaping up to supply one of the most valuable sources for the study of Preston history to have come available in many years, detailing just who owned what land and listing hundreds of field names, many of which can be traced back to the Middle Ages.

Who owned 19th-century Preston?