In this section of his book Bateman displays his anti-Irish and anti-Catholic prejudices, as in the following selections from his text:

In this the ‘merrie month of May’ chaos reigns in Ireland; in half that distracted kingdom the peasantry are now virtually owners of the soil,—paid for though it may have been, and in many cases was, with Saxon cash, the fruit of Saxon toil and industry.’

… the industrious Irish peasant, as I know him best in Co. Mayo, loves to work ten minutes, then to rest on his long-handled spade for another twenty, then perhaps he does a furious spurt of labour for a quarter of an hour, which deserves to be rewarded, as it generally is, by well-earned rest against the nearest cabin wall, and a pipe of tobacco as a soother, and so on ad lib. Irish soil for the Irish!

French peasants thrive; Irish peasants don’t.

French peasants work; Irish peasants won’t.

Yet, according to Roman Catholic lights, France ought to be a blighted and heaven-accursed country, where Gambetta exercises his wicked will over the priesthood, and mightily oppresses them, while our British Premier has taken the best of care to denude Erin of the only educated men who could hold their own against the rural Irish priest.

Appendices

I.—A table showing the distribution of the area of the United Kingdom among the great landowners themselves, divided into six classes.

| Class I. | No. of persons holding 100,000 acres and upwards | 44 |

| Class II. | No. of persons holding between 50,000 and 100,000acres | 71 |

| Class III. | No. of persons holding between 20,000 and 50,000 acres | 299 |

| Class IV. | No. of persons holding between 10,000 and 20,000 acres | 487 |

| Class V. | No. of persons holding between 6,000 and 10,000 acres | 617 |

| Class VI. | No. of persons holding between 3,000 and 6,000acres | 982 |

| Total | 2,500 |

This table excludes holders of large areas the rental of which does not reach £3,000; a list, however, of the more noteworthy of these exceptions is given further on. This and the following tables do not take in the Metropolitan area, the Isle of Man, or the Channel Islands, or the estate of the Hon. C. W. White.

| Holders of between 2,000 and 3,000 acres, or of between £2,000 and £3,000 rental from estates of over 3,000 acres | 1,320 |

This table, as well as Tables II., III., and IV., was compiled in 1879; the alterations which have since taken place in the distribution of English land would not materially alter it, or them. Some men have increased their wealth, or, in the expressive North country, phrase, “kept a-scrattin of it together,” while divers eminent firms of auctioneers have been kept busy dispensing the dirty acres of those more unfortunate or more lavish. In this the “merrie month of May” chaos reigns in Ireland; in half that distracted kingdom the peasantry are now virtually owners of the soil,—paid for though it may have been, and in many cases was, with Saxon cash, the fruit of Saxon toil and industry.

I may mention that, since the Premier has taken the détenus of Kilmainham into his confidence, but two Irish landowners have taken the pains to correct the figures contained in the body of this work. Are they in hiding in caves or bullet-proof huts? (they can hardly think that letters of inquiry dated from the Carlton Club are likely to contain dynamite); or do they consider that Irish proprietorship is so utterly illusory under the present regime that to correct is a work of supererogation?

II.—A table showing the landed incomes of such of Her Majesty’s subjects as possess 3,000 acres rented at £3,000 per annum and upwards, divided into six classes.

| Class I. | Landed incomes of £100,000 and upwards | 15 |

| Class II. | Landed incomes of between £50,000 and £100,000 | 51 |

| Class III. | Landed incomes of between £20,000 and £50,000 | 259 |

| Class IV. | Landed incomes of between £10,000 and £20,000 | 541 |

| Class V. | Landed incomes of-between £6,000 and £10,000 | 702 |

| Class VI. | Landed incomes of between £3,000 and £6,000 | 932 |

| Total | 2,500 |

| Holders of £2,000 rental and below £3,000 or under 3,000 acres | 1,320 |

III.—A list of some of the holders of exceptionally large estates, the rental of which is under £2,000 per annum.

[Table data not reproduced here: see original if needed] [1]

IV.—A list of the number of great landowners who are members of the following clubs:—

| Political Clubs | |

| Tory | |

| Carlton | 642 |

| Junior Carlton | 112 |

| Conservative | 65 |

| St. Stephen’s | 37 |

| Total Tory | 856 |

| Liberal | |

| Brooks’s | 216 |

| Reform | 103 |

| Devonshire | 29 |

| Total Liberal | 348 |

| Service Clubs | |

| United Service | 107 |

| Junior United Service | 72 |

| Army and Navy | 120 |

| Guards | 70 |

| Naval and Military | 22 |

| Total Service | 391 |

| Learned Clubs | |

| Athenaeum | 145 |

| Oxford and Cambridge | 79 |

| United University | 61 |

| New University | 16 |

| Total Learned | 301 |

| Other Clubs | |

| Travellers | 286 |

| White’s | 169 |

| Boodle’s | 145 |

| Arthur’s | 119 |

| St. James’s | 86 |

| Garrick | 55 |

| Turf | 54 |

| Marlborough | 52 |

| Union | 50 |

| National | 35 |

| Windham | 29 |

| St. George’s | 28 |

| Raleigh | 13 |

| Total Other | 1,121 |

Some changes have come over clubland since 1879. The “Scottish,” “Royal Irish,” “Bachelors’,” and “Salisbury” have, for good or evil, added themselves to the already lengthy list of clubs, while the “Junior Naval and Military” has resolved itself into a political club as the “Beaconsfield,” thus adding to the disproportionate number of Great Landowners who belong to Tory clubs; which disproportion is far more affected by the numerous (and somewhat late) secessions of Whigs who cannot stomach recent Radical legislation. In Liberal circles it is rumoured that the late internecine feud at the “Reform” has numerically strengthened the “Devonshire” not a little.

V.—A list of peers and peerages whose estates have been added to those of large-acred peers in the preceding table.

[Table data not reproduced here: see original if needed] [2]

VI—Tables showing the landowners divided into eight classes according to acreage—with number of owners in each class; and extent of their lands.

“Peers” include Peeresses and Peers’ eldest sons.”

“Great Landowners” include all estates held by commoners owning at least 3,000 acres, if the rental reaches, £3,000 per annum.

“Squires” include estates of between 1,000 and 3,000 acres, and such estates as would be included in the previous class if their rental reached £3,000, averaged at 1,700 acres.

“Greater Yeomen” include estates of between 300 and 1,000 acres, averaged at 500 acres. “Lesser Yeomen” include estates of between 100 and 300 acres, averaged at 170 acres.

“Small Proprietors” include lands of over 1 acre and under 100 acres.

“Cottagers” include all holdings of under I acre.

“Public Bodies” include all holdings printed in italics in the “Government Return of Landowners, 1876,” and a few more that should have been so printed, being obviously Public properties.

“Peers” and “Great Landowners” are assigned to those counties in which their principal estates are situated, and are never entered in more than one county. The column recording their numbers in each county must be taken with this qualification, but the acreage of all the “Peers” or “Great Landowners” in each county is correctly given, and their aggregate number, as well as their aggregate acreage, may be learned from the summary.

[The tables for counties other than Lancashire have been omitted]

| Lancashire | ||

| No. of Owners | Class | Acres |

| 10 | Peers | 135,322 |

| 36 | Great Landowners | 218,570 |

| 79 | Squires | 134,300 |

| 257 | Greater Yeomen | 128,500 |

| 692 | Lesser Yeomen | 117,640 |

| 10,845 | Small Proprietors | 168,100 |

| 76,177 | Cottagers | 14,811 |

| 639 | Public Bodies | 30,221 |

| Waste | 64,305 | |

| 88,735—Total | 1,011,769 | |

Summary table of England and Wales.

| No. of Owners | Class | Extent in Acres |

| 400 | Peers and Peeresses | 5,728,979 |

| 1,288 | Great Landowners | 8,497,699 |

| 2,529 | Squires | 4,319,271 |

| 9,585 | Greater Yeomen | 4,782,627 |

| 24,412 | Lesser Yeomen | 4,144,272 |

| 217,049 | Small Proprietors | 3,931,806 |

| 703,289 | Cottagers | 151,148 |

| Public Bodies | ||

| 14,459 | The Crown, Barracks, Convict Prisons, Lighthouses, &c. | 165,427 |

| Religious, Educational, Philanthropic, &c. | 947,655 | |

| Commercial and Miscellaneous | 330,466 | |

| Waste | 1,524,624 | |

| 973,011—Total | 34,523,974 | |

These figures are compiled from those at the foot of each County in the Return of 1873. They do not harmonise exactly with the summary at the beginning of the Blue Book, but that summary itself varies from the County summaries in many instances—in Durham, for instance, by some 2,800 acres.

These tables (and the dissertation thereon) were compiled for “English Land and English Landlords,” by Hon. George Brodrick, published by the Cobden Club in 1880, the dissertation being somewhat toned down so as not to offend men of extreme Liberal views.

NOTES ON THE FOREGOING TABLES

“Statistics!—why they may be made to prove anything,” said an eminent civil engineer to the Compiler a few weeks ago. “The London death-rate, for instance, is the greatest lie I know; for the bulk of the great middle class, as is well known to Doctordom, if it can possibly manage it, goes into the country to die.”

A lie of this kind was the original cause of the compilation of the much-abused “Return of Landowners, 1873,”—viz., that in the census tables of 1871 some 30,000 persons only were entered under the head of “Landowners;” which so-called fact was much gloated over by those who would fain apply Mr. Bright’s “blazing principles” to our existing land system. This lie vanished with the publication of the Government return of 1873, in the year 1876; the landowners being found to come to something like a million.

Still it was evident that, useful as this compilation might be, it was marred by several serious blots, such as the non-entry of the Metropolitan area, the omission, in some counties at least, of the woods which in 1873 were still unrated, and the occasional double entry of one and the same man, especially where he was blessed with a double-barrelled name, such as Burdett-Coutts or Vernon-Harcourt, to say nothing of grosser cases, where some four surnames are strung together, rope-of-onion fashion, like Butler-Clarke-Southwell-Wanderforde or Douglas-Montagu-Scott- Spottiswoode. A study of the Blue Book convinced me that something like 10 per cent., if not more, of the landowners thus appeared more than once; and, when compiling “The Great Landowners of Britain,” I wrote to every large owner begging a correction, the answers proved that my surmise was perfectly right.

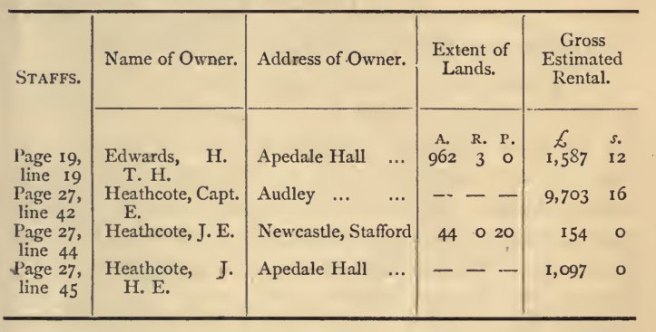

One instance may be given. Case of Capt. Edwards-Heathcote, copied verbatim from the Return (his real initials being I. H.):—

Capt. Heathcote’s real acreage is much over the amount with which the Return credits him. The property lies in at least four parishes,—principally in Audley, in which, I believe, Apedale Hall stands; and Newcastle is his post town.

Having considerably weeded out these double, treble, and multiple entries before compiling “The Great Landowners,” I have used that work, as well as the Government returns, in compiling the foregoing tables, using only such corrections as had been sent up to Christmas, 1877, but none of later date. Curiously enough, these corrections would not materially alter the totals in each column, because the cases of over-estimation in the Return are very nearly balanced by others which tell in an opposite way.

The 3rd Class (squires), and the 4th and 5th (greater and lesser yeomen) are averaged on the scales of 1,700, 500, and 170 acres, in all cases but Cambs., Northumberland, Rutland, Staffordshire, and Merioneth, where, if the usual averages had been strictly adhered to, the result on Class 6 would have been to make a “small proprietor” in Cambs. owner of but eleven and two-fifths acres, whereas he really holds 16 and one-sixth; while a Northumbrian in the same class would have been lord of nearly 50 acres. Suspecting this to be false, I worked out the actual extent of the lands held by the “squires” on Tyneside, which proved them to hold 355 acres apiece more than their fellow-squires nearer Cockaigne.

As to Staffordshire, a county very familiar to me, the staggering fact came out, after totalising the lands proper to each class, that the 6th Class landowner in Staffordshire was the pariah of his race, and not only a pariah, but one degraded so utterly as to be owner of but eleven acres; while a semi-Cockney of the same class in Surrey, which county most nearly approached him, held 13 acres of the soil. Still, though every statistical dodge has been tried to raise the 6th Class Staffordshire pariah from his low estate, every dodge, though it somewhat softens down his evil case, still fails to rid him of his disgrace. He, as owner of but twelve and one-fifth acres, is still the pariah of England.

The fact may perhaps thus be accounted for. At a very rural petty sessions in Northern Stafford, colloquies like the following were often taking place:—

MILD ASSAULT CASE.

Chairman of Justices loq.: “Prisoner, we have decided to convict you. You had no business to take the law into your own hands, and to give the man (though we must own you had much provocation) two black eyes, to knock him down, kick him, kneel on his stomach, throw his hat into the fire, knock out the ashes of your pipe into his left eye, and, finally, to use very bad language towards him.”

Prisoner: “Noh, sur, A knows A didna oughta a doon it—leastways, not quoit so mooch on it; but ye see, sir, A wasna ‘ardly sober at the toime.”

Chairman of the Justices(severely): “Drunkenness is no excuse.” (To Head Constable): “Shallcross! what’s this man’s position?”

Shallcross: “Milks three caaws, sir.”

Prisoner: “A dunna: you’re a loiar.”

Chairman of Justices (excitedly): “Really! you mustn’t,” &c.

Prisoner: “But A ony milks two—t’other’s a cawf.”

Chairman (after consulting Colleagues): “Very well, then, we fine you fifteen shillings, or twenty-one days.”

This police case only illustrates the fact that in the humbler walks of life, in both Cheshire (a small-averaged county) and Staffordshire, the position and respectability of a man is gauged by the number of cows, or rather “caaws,” he milks.

To my certain knowledge, there are hundreds, nay thousands, of colliers who hold from four to eight acres, milk two or three cows, and willingly slave in the pits or iron-works to provide the rent in case they are tenants, or the interest on the inevitable mortgage in case (as 33,000 of them are) they are freeholders.

The prevalence of this mania for cow-milking as the badge of respectability in Mercia, as contrasted with the counter mania for the same badge in the form of keeping a “servant gal” or a “one-oss shay” in Middlesex, accounts for the large number and small extent of Mercian sixth-class holdings. Rutlandshire is greedily seized upon by the host of pundits who have dilated on the Government Return as a text to preach a statistical sermon upon, viz., by The Pall Mall Gazette (of yore), The Spectator, Mr. Frederick Purdy,—Hon. Lyulph Stanley, M.P., Mr. Lambert, and others whose names have escaped me,—or at least by most of them; ’tis a tempting text—only four and a quarter pages long, as compared with 185 for York—but to me the sermons in figures thereon preached seem, like the London death-rates to my host of last August, to savour of the lie statistical. Rutlandshire folk may be estimable, astute, or both, but somehow they have not managed to keep possession of the acres, of all others (Leicestershire not excepted), most glorious for a fox-hunting gallop.

For instance, among foreigners owning their soil are the following:—

Adderley, Sir Charles (now Lord Norton, a Warwickshire man).

Aveland, Lord (who is classed as a Lincolnshire Peer, his principal property being there).

Belgrave, Mr., of Maydwell, in Northamptonshire.

Brooke, Sir W. de C., Bart., also of Northamptonshire.

Hankey, Mr., of Balcombe, Sussex. Lonsdale, Lord, from the North Country.

Northwick, Lord, a Worcestershire Peer.

Richards, Mr. Westley, of Birmingham (name dear to lovers of the trigger).

Exeter, Lord (who is classed as a Northamptonshire Peer).

Pochin, Mr., of Edmondthorpe, Leicestershire.

Pierrepoint, Mr., of Chippenham, Wilts.

Rutland, Duke of, a Leicestershire Peer.

Kennedy, Mr., “of London” (a somewhat vague address).

De Stafford, Mr., a Northamptonshire man.

Blake, Mr., of Welwyn, in Herts.

Laxton, Mr., from Huntingdonshire.

These sixteen persons among them own nearly 37,000 acres, or two-fifths of the whole county.

Again, the unwary statistician who can only succeed in finding five persons ranging from 1,000 acres to 5,000 might be misled by supposing that “Mr. Fludyer,” who figures for 1,100 acres, and “Mr. Hudyer,” who owns 1,500, are two separate persons; whereas Sir John Fludyer tells me that he is the person aimed at in the Returns of 1873, under both the letters F and H.

Where landowners only reach five in the third class, a mistake of one is serious, and any generalization therefore based on Rutlandshire alone would affect England as judged thereby to the extent of one-fifth at the least.

Merioneth deserves special distinction as exemplifying Class 6 in its highest stage of ownership; yet a walk through two counties would bring a wayfarer from this paradise of small proprietors into Staffordshire, its lowest type of degradation. A glimpse at the column devoted to “waste” will show the reason why— a reason in itself sufficient to prove that the parochial magnates who compiled the crude materials for the Return had many curious eccentricities. “Waste” figures for only 416 acres in Merionethshire—certainly a most bucolic part of the Queen’s dominions, if not exactly (as may be said of Connaught or Wester- Ross) “west of the law.” There is no doubt that a dozen spots could be picked on its wild mountain ranges where no policeman could be found within half-a-dozen miles. Contrast this with the neighbouring counties of Brecon, Denbigh, Montgomery, and Radnor, where the waste reaches a total of 215,000 acres, or say, 3,000 acres each. Yet Merioneth is a wilder county than any of the four. The obvious moral is that in Merioneth all joint lands have been equally divided in the rate-books among the participants, while in the four neighbouring counties they figure not as joint, but as waste lands. As to waste, though no uniform system of excision from other lands has been adopted in the Return, it may be roughly taken as a fact, that generally (but by no means always) they include, in the southern counties, heaths, charts, unfenced land, and, in some cases, salt marshes; and, in the northern ones, all such land as is entered in the valuable agricultural returns published of late years annually as “mountain pasture” and “barren heath.” But on what principle can one reconcile figures like the following:—Kent—waste, five thousand odd acres, Surrey—forty thousand? Kent is more than twice the size of Surrey, and as a fact contains, though perhaps in smaller proportion to its area, quite as much “heath,” “common” and “chart” as Surrey. We must guess that in the rate-books of Kent these wastes swell the estates of the local Lords of the Manor.

The northern counties contain vast areas of “waste.” Much of this is “waste” only in name, being unfenced, heathery-furzy-ferny-swampy-rocky pasture, much of it at a level of some 1,000 to 2,000 feet over sea-level, and affording fair pasturage to the hardy local sheep and cattle, though useless as nourishment to a 3,000 guinea shorthorn. These “wastes” are locally divided into what are called cattle-gates, each gate representing sufficient summer feed for one beast. In Kendal, Hexham, or Carlisle such cattle-gates are as saleable as an “eligible building plot” is in Kennington, Hoxton, or Camberwell; in no sense are they wastes; they are rather the rough survivals of some fossilized communal land system.

Let me with true Tory barbarity banish a few of the south-country land-law agitators, to try the experiment of settling themselves as virtuous and contented agriculturists on five-acre plots, carved out of the braes of Skiddaw, treeless, undrained, exposed to all the winds, and handsomely fenced with rough posts and rotten colliery rope. I fear the contentment would vanish, whether or not the virtue should remain. The agitator (specially if eloquent) is a proverbially thirsty soul: picture his horror at finding the nearest beer-house eight miles off, and the friendly grog-shop another five! Meanwhile, let him bear in mind a few simple facts—that in the northern counties he may have to keep his wife and bairns without such aids to digestion as onions, gooseberries, strawberries, carrots, apples, cherries, cabbages, and peas, none of which flourish in Northumbria over the 1,000 feet level, besides combining all trades in his own proper person—such as stonemason, waller, butcher, plasterer, shoemaker, painter, glazier, and possibly accoucheur. The case of the southern wastes is equally unpromising in a money-making or self-supporting point of view. Many a Kentish “chart,” if parcelled out into ten-acre freeholds, would scarce support a four-year old baby with a healthy appetite on each of them. Their only advantage over the northern moors is their much larger allowance of bright sun- shine—a commodity of which the supply is now regularly registered in the daily weather reports.

Irish ills, Irish grievances, we hear not a little of these nowadays: one grievance under which St. Patrick’s protégés suffer is often overlooked, i.e., the want of bright sunshine.

Lord Beaconsfield, touching on matters Irish, alluded to this when he spoke of “The incessant rain-drip on shores washed by a melancholy ocean.”

Ireland is Nature’s buffer and umbrella to break the wild violence of the storms so oft and so unkindly sent us from New York, and the gutter to carry off the superfluous rain. England thereby benefits. Western England gets oft-times more than it desires of rainfall. Corn-growing is but a secondary interest there. Cattle and cheese make the profits, and pay the rents. Irishmen should follow suit; instead of increasing the numbers of a starving peasantry, and glueing them to the soil, they should leave the ungrateful soil to itself, and to the cattle whom it could, under an intelligent system of breeding and rearing, carry with ease; or if they must continue to cultivate the soil, cultivate it where the sun does occasionally shine often enough to ripen a crop of oats—or something better.

Meanwhile, the Irish coasts swarm with fish which they seldom even try to catch. Any capitalist who introduces a new manufacture or handicraft is sure to suffer in purse, even if he escape a bullet in the head.

Why, again, may I ask, is it that an Irishman will only dig a pratie out of his own easily dug, friable peat soil? He does not care for the same job on the stiffer lands of New York, Ohio, or Illinois. No; he severely sticks to town life and its joy, the whisky-shop; he hardly even enters the country parts of Yankee land. No; the industrious Irish peasant, as I know him best in Co. Mayo, loves to work ten minutes, then to rest on his long-handled spade for another twenty, then perhaps he does a furious spurt of labour for a quarter of an hour, which deserves to be rewarded, as it generally is, by well-earned rest against the nearest cabin wall, and a pipe of tobacco as a soother, and so on ad lib. Irish soil for the Irish!—hurrah, t’would demean a bold peasant to delve in stiff clays, such as the East Saxon hirelings of our East Saxon agricultural prophet, Mechi, delve and moil in, from six till six, or something like seven hours more work than the most industrious Galway or Mayo man ever did in a day.

French peasants thrive; Irish peasants don’t.

French peasants work; Irish peasants won’t.

Yet, according to Roman Catholic lights, France ought to be a blighted and heaven-accursed country, where Gambetta exercises his wicked will over the priesthood, and mightily oppresses them, while our British Premier has taken the best of care to denude Erin of the only educated men who could hold their own against the rural Irish priest.

The climate of these islands, I fear, is not suitable for what the French call “the small culture.” No man on an average British plot of 2½ acres can raise and support a healthy family. I would put the smallest desirable peasant-holding at from 4½ to 6 acres, and these only in the eastern—i.e., the drier—half of England. In the western counties, where the bulk of the land is under permanent pasture, and corn-growing is a secondary interest, the minimum should be raised to what would keep four cows; and this minimum would vary much in different counties—say from 9 acres in the vale of Evesham, to 45 or 50 in north-western Devonshire. Desirable as it is in every way to encourage the subdivision of the soil on political grounds, specially from the moderate Tory point of view, it cannot be too strongly urged that if a man buys a small freehold (as we all hope he may be able to do when Sir Charles Dilke carries his intended (?) measure for the hanging of all conveyancing counsel and solicitors whose deeds of conveyance exceed 40 lines), that man should have some other trade or means of livelihood than the tillage of the soil. We cannot stand an indefinite increase in the number of acres under such crops as lettuce, radishes, cabbage, celery, and onions; the supply would soon exceed the demand, and the cultivator would starve. 217,000 “small proprietors” are already in our midst—men who own some twenty acres apiece—and it will be well for England when the number is quadrupled. Beyond that point it would so far do harm as to (I believe) materially reduce the amount of food grown on the fair face of Old England. In view of the terrible competition of American produce, large capital, open-handed use of all manures, close-fistedness in bargaining, and credit enough to avoid having to sell at bad prices, combined with a largish area to work on, and much knowledge of the business, are the only conditions under which the British farmer can hold his own. Men of this stamp are far too wise to aspire to the ownership of the lands they till.

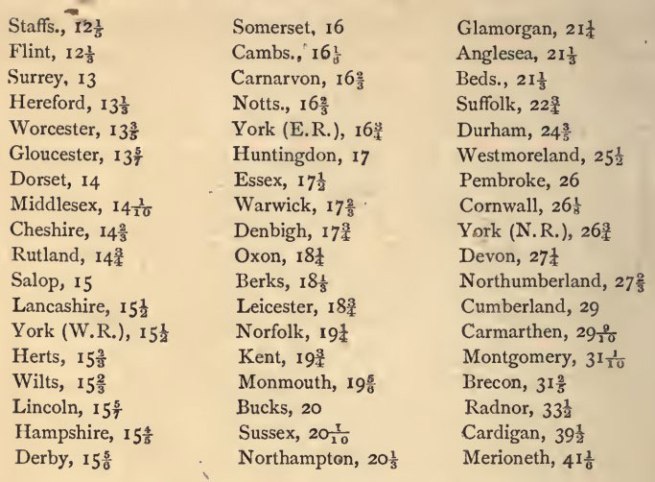

When divided by the number of small proprietors in Class VI., the four million acres they hold shows the following approximate average size of holdings in each county:—

It may be noted how closely the averages of many neighbouring counties run—the four northern counties and their neighbour, the North Riding; the three cider-making counties of Gloucester, Hereford, and Worcester; Lancaster and the West Riding; Kent and Sussex; and, though divided by the “silvery Thames,” it is hard to raise a distinction between a small holding in Oxon and its fellow in Berks.

The two classes of yeomen show also a few curious facts; notably, the very large proportion of them who have the prefix “Rev.” to their names. Of course it may so happen that in some parts of the country the rate-collectors, following the example of the Vicar of Owston and his Diocesan of Lincoln, refuse this prefix to our non-performing clerics, and thus simplify the labour of cleric-extraction from the ranks of the yeomen; but I take it that as a rule not only “Church Parsons,” but their brethren “Ministers of Religion” who so often (and wisely) are associated with them in the modern toast-list, and even “Holy Romans,” are entered in the Return of I873 as “Reverends.”

Their total number is 3,185, out of a total landed yeomanry of 33,998; in other words, not far short of ten per cent. Names with the clerical prefix are thickest in Northampton, Leicester, and Rutland, where about one in five of my yeomen is a cleric. This, of course, means that the glebe-land has not been entered, as the Local Government Board directed, as the property of “The vicar of Blank,” but in the vicar’s name, as “Rev. J. Smith.”

After all, “yeomen” is but a makeshift title for holders of between 100 and 1,000 acres. If called out for a yeomanry drill, ‘twould be diverting not a little to see, dressed in line, Mr. Goschen (halting between two opinions), Sir R. Cross (smiling on his neighbour), a popular Protestant Dean, arguing a theological point with the Ex-President of the E.C.U., while his rear-rank man, Mr. Coupland, who rules in Leicestershire, might talk fox-hunting with the Poet-Laureate and an eminent Hebrew financier. Still, as no better name suggests itself, we must content ourselves with calling them “yeomen.”

It is much to be hoped that, if ever a revision of the Great Return of 1873 is made, a separate volume will be given to all town properties, as it is essentially absurd to mix the rental (say £10,000) derived from a row of warehouses in Bristol, covering three acres, with £50 more derived from fifty acres of Gloucestershire clay. This is always done in the present Return; thus—

Extent, 53 acres; rental, £10,050

Let us also hope that, ere then, our rulers, even if they do not proceed to the violent measure with which I have saddled Sir Charles Dilke, will shatter the legal bonds which fetter and prevent the free sale of land, and the expansion thereby of Class 6—a class which, if multiplied fourfold, would add greatly to the stability of our fatherland and its institutions. Could they but effect this (I could hardly say so much in 1882), I for one (Tory though I be), shall not regret that, for what I hope is but a short space, the tree-planter of Hughenden succumbed to the woodcutter of Hawarden.

JOHN BATEMAN

Carlton Club,

October, 1880

Who owned Lancashire – introduction

Bateman’s Great Landowners – Preface

Bateman’s Great Landowners – Lancashire

Lancashire’s resident ‘great landowners’

See also:

Great War conscription and Edwardian Preston’s ‘class ceiling’