Notes

- The dense, lengthy paragraphs of the original have been broken up for improved readability.

- The map sections that illustrate the route are taken from the Ordnance Survey six-inch map first published in 1849, with some later additions such as, for example, St Walburge’s Church opened in 1854.

- Spellings have not been corrected, except for proper names, to avoid sprinkling the text with the ‘sics’ beloved of pedantic scholars.

- Words now rarely found are defined on their first appearance.

- Images of the various places and streets mentioned can usually be found in either the Preston Digital Archive or the Red Rose Collection.

- For detailed histories of any of the public houses mentioned see Preston’s Inns, Taverns and Beerhouses.

The cotton manufacturing districts represent their exigencies in architecture in a remarkable manner. The factories might be oblong packing-cases of brick and mortar, pierced with rows of oblong window openings; and shooting up from this tasteless block is a tall chimney-shaft. Grouped with these, like young factories not yet arrived at maturity, are rows and rows of habitations for the workers, —also oblong, also pierced with oblong windows, only on a smaller scale, and with the chimney-shaft not developed beyond the size of ordinary cottage chimneys.

Nothing plainer could be conceived. The granaries in which Joseph stored the Egyptian corn could not have been built with greater frugality; but, as the manufacturing of cotton into fabric is not with us an ancient occupation, these are all comparatively modern; and the veritable town, as it was of old, lies among them like a tangled skein of thread.

Preston is one of the towns to which Henry II granted a charter to the effect that the burgesses should appoint a guild merchant, who, ‘with the burgesses, should enjoy “all liberties and free customs”, that is, that they might pass through the royal dominions with their merchandise, buying and selling, free from all kinds of toll; and that in their own town they might exact, receive, and enjoy, as the case might be, the following penalties and privileges, —“all manner of security of peace, soc and sac, toll, infang-thief, outfang-thief, hang-wite, homesokyn, gryth-bryce,flight-wite, ford-wite, fore-stall, child-wyte, wapentake, lastage, stallage, shoowynde, hundred and aver-penny.” And interspersed with the modern commerce and traffic, there is yet much that is associated with these royal, pictorial, heraldic, and traditional times.

Nevertheless, the great enlargement of the town and increase of the population are due to the modern business of cotton-spinning and weaving. It is these that have enriched the owners of land and capital alike. Directly a factory has been planted down, the land has been turned up for brick earth, a kiln started, bricks manufactured, and rows of poor houses built,—profits being obtained both from the manufacture of the bricks, and in the shape of rent subsequently.

The wants of the operatives are few in their homes; and it is only common humanity on the part of the wealthy factory and landowners that these should be provided for. The workers cannot be expected to be refined or even decent, if the homes in which they are reared be destitute of decencies; nor can their children be expected to play anywhere but in the streets if there be no yards to the houses, no public playgrounds, nor public parks. We will see for ourselves, presently, how these responsibilities are recognized.

Neither tradition, politeness, nor truthfulness can call upon us to admire the exit from THE RAILWAY STATION from the departure side for London, Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester, Wigan, and Bolton, by the first and second class booking-office entrance, which is in a coke-shed. It is grimy with coke-dust; all the painted work resembles stucco, as the surface of it is raised with particles of coke dust, which must have settled upon it before it was dry; and the sweepings of platform and offices—dust, scraps of paper, envelopes, and such litter—are lying on the road.

For “the way out” there is a choice of two roads, one for vehicles to the right, in the direction of the goods department—the same road serving for passengers’ vehicles and the goods waggons, whereby it gets dreadfully cut up,—and another for pedestrians, up twenty-six wooden steps, which are under cover of the same coke-shed. At the top of the steps is a long gallery, with an inclined floor, looking, with its bare walls and flat ceiling, like the entrance to the gallery of a theatre. The plaster, which is grey with coke ash, is coming off the walls in patches, and not a time-table, nor a placard, relieves its long monotony. There is, however, a railing up the centre, which is apparently provided for a crush, or for division of classes, at excursion times, and which causes uncomfortable conjectures to arise as to the safety of a descent of twenty-six steps in the way of a crowd of the kind.

The tubular gallery discharges the passengers into a carriage-road which is used alike for goods and passengers, is wretchedly paved, and never swept. A board declares that no rubbish is to be shot [?] here; clothes are hanging out to dry; and the ruins of the gate-posts of the entrance gateway are lying about—great blocks of stone. On the boundary-wall, so that you may read as you hurry along, are posted placards, inscribed with pithy ejaculations bearing upon the incidents of the ward elections,—“Jolly doings in St. Peter’s ward! Beer and bribery for ever! ! Remember Miller the just. No coalition between Gudgeon and Whitehead.”

And beyond the ruined and neglected entrance is the advance guard of the town, a short street of beershops [BUTLER STREET]. This street paced, we are in the main thoroughfare of the commercial part of the ancient borough of Preston,—FISHERGATE.

This is an irregular street about two miles long, which was one of the old roads, in the old town, to the market-place. The low, thatch-crowned houses with which it was once lined as it neared the market-place have disappeared, except in one solitary instance; and have been replaced from time to time by the shops, hotels, banks, and offices, needful to modern commerce.

The VICTORIA HOTEL is the first object noticeable in Fishergate; and then a large tenantless house next door to it, with centre and wings, looking as a haunted house might be expected to look of a November morning.

On the other side of the road is a row of staid houses, with gardens fenced with iron railings in front of them that are one yard wide. These few feet of spongy soil thus pertinaciously tilled in front of town houses admit of rain soaking into the foundations: they can scarcely be considered to be ornamental, except perhaps for a week or two, when newly done up in the spring; and for the rest of the year are dismal and damp engendering. If these spaces were paved much damp would be done away with, and floral effects might be obtained in boxes on the window-sills.

Then there is a vacant space on both sides of the road, with a few forlorn trees and a bridge over a grass-grown single iron tramway. This unbuilt piece of ground is occupied, as so many others now are, by a travelling photographic portrait- room—a smart caravan containing two if not more chambers.

It is from this point of view that the peculiarities of the cotton district, as shown in the aspect of the town, are first discernible. Fishergate runs along a ridge; and, whenever there is a gap in the houses, a view of the factories in the surrounding hollows is obtained; and this is the first glimpse on the road from the station. The factories are piled up story above story and group against group, the tall chimney-shafts keeping guard over all; and the squat houses of the operatives are spun out in rows around.

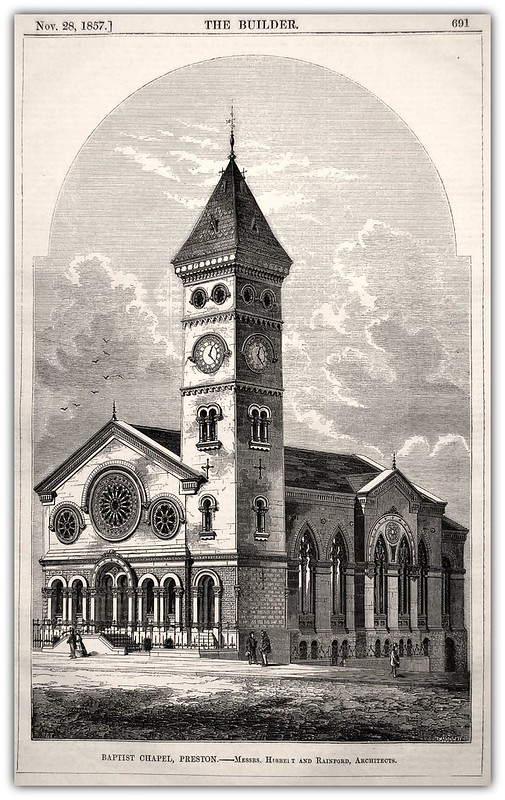

A little way further on, at the corner of CHARNLEY STREET, there is a new BAPTIST CHAPEL, which, with its tower of bold Venetian type, would be an ornament to any perspective. The style is Romanesque, with Moorish details. A great wheel window in the north end, surrounded by circles, with a miniature repetition of the same on either side of it, is remarkable for much effect with very little light—much stonework and little glass—but which arrangement is admissible on account of the site being a corner one: plenty of light can be obtained at the side. The clock, too, with its illuminated faces on the sides of the tower, is a real boon. The iron balustrade and stone parapets in front are carefully considered in relation to the style of the rest of the building. The front is set back from the line of houses—a disposition which not only shows the building to advantage, but improves the aspect of the street. [The chapel was built in 1857, the property it replaced is shown on the above map. The architect’s drawing of the chapel above was published in The Builder the same year].

This specimen of the highest class of architectural art is the more conspicuous by its neighbourhood of plain houses, and a contrast to the hideous box of a theatre on the opposite side of the road [THEATRE ROYAL].

A sewer pipe stuck on end, with a long stick standing upon it, indicates that something is going on in the rear of WILFRED STREET—a row of neat-fronted houses; and turning down to see what it may be, we find 17 privies, 17 offal ash-pits, and 17 slop- drains, built up against the 17 neat-fronted houses in question. These harbours for filth have soiled and choked the ground till they could be borne no longer; and drain-pipes are being laid down.

The men putting down the pipes, in the cuttings made for their reception, declared that this was the dirtiest place they had ever been in. Below the pebble pavement, which looked so smooth and regular, and extended from one end to the other, in the rear of this row of neatly-fronted houses, the soil for several feet was a mass of foetid corruption,—too thick to bale out, yet with not enough consistency to shovel up,—vile and filthy.

This state of things is at the core of all similar cesspool arrangements: —the surrounding soil absorbs the moisture from privies and ashpits, and thence it percolates through houses, and streets, and alleys, till it finds a low level to form a pool; and, from this highly-charged soil, emanations arise that are conducive to the breeding of fever. In this particular instance there is a “public bakehouse” close by, to make matters worse.

Returning to FISHERGATE, we note the iron vase on the iron pedestal in front of the THEATRE ROYAL, that is complimentarily called a drinking-fountain; and the doctor’s red lamps that light up the miniature portico, and a desire to see more of art in Preston, induce us to make, in the evening, an examination of it within. To save recurrence, we may state here that the ceiling is divided into eight compartments, radiating from a sun-burner in the centre, with a figure disporting in each compartment. The boxes over the proscenium are hung with bed-curtains, and look quite as much like berths on board ship; and the decorations generally are in what might be called the paperhanging style.

The form of the theatre is good; and, with artistic decorations, might be made attractive and effective. The scene-painting deserves a word, the landscapes being good enough to atone for the miserable interiors, where the paperhanger had evidently all his own way again. The audience, composed of factory operatives, occupied the pit and gallery, and brought their babies with them. The performance comprised the “Colleen Bawn” and the “Artful Dodger,” with a comic song between the acts; and when we add that Grisi was prospectively expected, it will be seen that there was but little to find fault with.

The pavements in FISHERGATE are especially commendable; where the pavement widens at MOUNT STREET it is 18 feet broad. The curbs at the crossings are rounded and gradually sloped, without the ordinary sudden step and the crossings are made of large blocks, with a grove in the centre.

At CHAPEL STREET we strike off to view the huge one-span plain lofty brick room, which is used as ST. WILFRED’S ROMAN CATHOLIC CHAPEL. Internally a theatrical effect is produced by the altar recess being kept dark, except where, by means of an invisible skylight, a stream of bright light falls upon the altar picture of the Crucifixion, with an awe-striking effect. The whole of the interior, the walls, the flat-coffered ceiling, the fronts of the galleries are covered with a Grunerish stencilled decoration [Lewis Gruner – ‘Engraver, art expert and historian. Active in Germany and Britain (1841-56’. (https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/name/ludwig-gruner)], interspersed with medallions, a manner which gets over the difficulty of decorating a plain flat surface, in a large galleried room, satisfactorily.

CHAPEL STREET leads to WINCKLEY SQUARE, the garden part of which is large and sloping to a hollow, in which vegetables are cultivated and clothes hung out to dry. This piece of utilitarianism is scarcely called for, and must be an eyesore to the handsome houses at the upper end of the square, including Nos. 20, 21, 32, and 23. At the corner of the square and CROSS STREET, the Philosophical buildings [the LITERARY AND PHILOSOPHICAL INSTITUTION] and GRAMMAR SCHOOL form a showy pile in the Late Domestic Perpendicular style in fashion some few years back; full of movement, with bold projections and recesses, buttresses and oriels, traceried window-heads and good carving.

The octagon turrets to the entrance of the Grammar School are surmounted by Moorish tops, and the deeply-recessed doorway is as massive as the entrance to a castle. The Philosophical buildings of themselves would have formed but an inconsiderable group, but these assimilated with the Grammar School a noble pile is gained. This is an instance of the great advantage of clustering public buildings together.

In the playground of the Grammar School we were sorry to see that the four corners were converted into open urinals by the boys. In the street, too, open channels are running with soapsuds across the pebble pavement, and a general want of scavenage [street sweeping] is apparent.

An Italian villa occupies the opposite corner of CROSS STREET, and a STATUE OF SIR ROBERT PEEL stands within the railings of the square at this point; so that want of neatness in the road and footways, and the planting of vegetables in the square, are blemishes to a very good neighbourhood.

Returning by WINCKLEY STREET, we pass the Coroner’s and County Court offices, which are shabby, dirty, old buildings; and get back again into FISHERGATE, near to the cheerless-looking DISPENSARY.

After this LUNE STREET crosses at right angles, and owns a newly-enlarged grand WESLEYAN CHAPEL, and the CORN EXCHANGE, and Cloth Hall. This latter, however, is not a building that strangers need seek to see. It was built in 1832 [it actually opened in 1824], and is as ugly as even the level of public taste at that time can account for; having pig shambles at one end, and fishmongers and shrimp dealers at the other. The approaches, in a neighbourhood of bonded warehouses and of a large timber-yard, are scandalously in want of scavenage, and all the doorposts are made use of as urinals. There is the triple accommodation of a public room for concerts in the same building, which holds about six hundred persons: it is a long, low room, divided into three compartments, with pink and green flat paper panels; and owing to the floor being level, but an indifferent view of the performers at the upper end of the room is obtained from the entrance; the whole establishment being but a sorry affair for a town like Preston.

FISHERGATE still stretches out bravely before us, with bonnet-shops, booksellers, and bootmakers, side by side with the palatial PRESTON BANKING COMPANY’s premises—a costly, lofty, highly decorated, three-storied, Italian building—dwarfing its unpretending neighbours the chandler’s, chemist’s, hairdresser’s, tailor’s, and butcher’s shops. Then the PRESTON PILOT OFFICE, in CLARKE’S STATIONER’S SHOP; another stationer’s at the side of it; and the LANCASTER BANKING COMPANY’s offices, more modest and staid than those of the Preston Banking Company, yet equally tall and effective.

On the other side more chemists, hairdressers, upholsterers, drapers, and glovers’ shops; and here BUTLER’S SHOP, full of Roman Catholic accessories, sculptured and pictorial crucifixes—ivory, ebony, brown wood, and bronze crucifixes of all imaginable sizes—by the side of the KENDAL BANK.

By the side of the Lancaster Bank is a very narrow street [?] of very low houses, occupied by surveyors, land agents, valuers, a beadle, a sheriff’s officer, a beer-shop, and a tailor; down which flakes of soot are flying and settling on the cracked, bad pavement, in which channels are made in communication with external wooden spouting to the houses.

Beyond this, among the smart shops in Fishergate, stands a thatched house, with bulged plaster walls—the last vestige of old Preston in this bustling stream of modern traffic. Past the SHELLEY’S ARMS there is a very neat butcher’s shop, formed of three round arches with iron grilles and plate glass sliding windows. Within, the table top is covered with marble. If the walls were lined with white tiles, instead of coloured a dirty sallow brown, this would be a model of a butcher s shop, and prove that shop-fronts for this business can be made architecturally tasteful and suitable.

More shops—feather-shops, baby linen warehouses, watchmakers; more courts—dismal, dirty PLATT’S COURT; light and well-paved WOODCOCK’S COURT, scented with an aromatic malt-ous odour. The offices of the PRESTON HERALD Company (limited); the offices of the PRESTON CHRONICLE opposite; THORP, BAYLESS, & THORP’S GREAT DRAPERY ESTABLISHMENT, with a row of ventilating funnels behind the iron balustrade over the shop-front; a narrow alley with “JAMES LEIGH, BREWER,” at one corner of it, and a small butcher’s shop at the other, and a full ash-pit seen in the midst thereof from the main road. Then CANNON STREET, branching off, with HOGG’S FRUIT AND GAME SHOP at the corner, where pheasants and hares hang in festoons; partridges, pine apples, grouse, and grapes are grouped very artistically; then mat and matting shops, china shops, and the PRESTON GUARDIAN office, at the corner of new Cock’s yard [NEW COCK YARD]—which yard leads to the NEW COCK INN, and is used as one wide urinal, the miserable pebble pavement being full of hollows of slops.

At last the TOWNHALL narrows the road, just where CHEAPSIDE leaves Fishergate at a right angle, and the market-place opens out in view. The Townhall is neither modern nor ancient; but is a dingy worn-out mansion. The entrance immediately faces an alley 3 or 4 feet wide, by the side of the “LEGS OF MAN” inn, down which is a dirty perspective. BREWSTER AND BURROWE’S double shop is a noticeable feature from this point: it is a draper’s shop below; and above, the first floor has been taken out and another shop front, displaying cabinet- maker’s goods, placed in its stead. We are familiar with show-rooms over shops; but this is shop above shop. The rear of the Townhall is open to the market-place, and is ragged, tasteless, smoky, and dirty. Shop shutters are leaning against the ruined walls, as are temporary wooden urinals; and placards and posters are stuck upon every available space.

The MARKET PLACE is a handsome roomy parallelogram, surrounded on two sides by good shops, inns, and hotel; by the Townhall on the third; and by a row of shops on the fourth side, which is broken up by alleys leading to the shambles in the rear of them. Hay seeds, hay, and straw, are scattered over the pebble pavements; and on the off market-days the great open space is occupied by a few odd vegetable stalls on trestles, with movable wooden canopies. As we look on, a rag fair is held—one man selling remnants of highly-coloured, painted and glazed calico, odd bits of cloth, fragments of white linen; another man selling every possible description of cheap haberdashery, reels of cotton, combs, pins, needles, &c.; and both spread their wares upon the ground. It is impossible to be unimpressed with the capabilities of the site.

If the Townhall were rebuilt; the row of shops with the butchers’ shambles in their rear, with all the narrow courts intersecting this block of building, removed, and a meat market built instead; the block of houses on the north side of the market-place removed, and a general market built on its site; Preston would be able to boast of one of the finest market-places in the kingdom. We were glad to hear that the market committee were in consultation with Mr. G. G. Scott upon this subject. But the drainage and paving should not be overlooked in favour of more showy accommodation.

The gutters in the market-place run with slops thrown out of the houses in the courts around; channels across the pavement in CLAYTON COURT—channels from urinals in a passage to the BLUE ANCHOR—channels in passage to STRAIT SHAMBLES,—all furnish tributaries to the stream down the market kennel [‘The surface drain of a street; the gutter’ (OED)]. WILCOCKSON’S COURT does the same: GINBOW ENTRY, leading to the WHEATSHEAF and WHITE HART, brings down the swimmings from exposed urinals and stable muck; and washings from the shambles are flowing down all the livelong day.

STRAIT SHAMBLE[S], one of the passage ways in the block of shambles, may be taken as a type of the rest,—lines of close butchers’ shops, running at right angles from the market, with a dark living-room in the rear of each, and a smaller and darker sleeping-room above. The washings from the blocks are finding channels down to the lowest level; losing on the way great part of their bulk, which is absorbed into the soil.

And so we pick our way round to the principal facade of the shambles in LANCASTER ROW. This is recessed back: the upper part projects over the lower, and is supported on rude, monolithic, tapering pillars, out of the perpendicular. The brickwork above is dirty white where it is not dirty black: the windows are very small, and filled with small panes; and the whole place has an uncouth and unclean appearance.

The POST OFFICE is near the shambles, and contrasts very favourably with them, being in a block of newly-erected lofty houses exactly opposite: it is roomy and convenient. Attached to the STANLEY ARMS, in the same block, is a notice-board, inscribed, “Police regulations. Make no wet.” And yet at the end of the hotel there is an unprotected urinal; and, unprovided for by drainage, the urine flows across the pavement in a broad stream.

A long, old-fashioned, winding thoroughfare, called FRIARGATE, straggles away down hill from the market-place. This is a long tortuous street, of second and third rate shops, to supply the wants of the dwellers in the innumerable courts and alleys with which it is intersected. In the main street scavenage does not appear to be thought of; and in the alleys and courts the laws of boards of health are set at defiance.

The rear premises of both sides of Friargate, which is about a mile long, and, starting from the market-place, is in the centre of the town, are horrible masses of corruption and forcing pits for fever. In FISHWICK’S YARD there are three vile privies and a crammed offal-pit close to the wretched houses, which, with their broken paved and damp floors, are scarcely fit for human habitation: and the overflowings from slops of another row of houses run down the yard. Four more dreadful pits at the end near a back lane are piled full, and leak across the alley into Friarsgate.

These are the characteristics of all the courts and passages in the neighbourhood: some of them, such as HARDMAN’S YARD, at the corner of the newly-painted WATERLOO INN, are whitened and made showy to look clean about the entrances; but step past the whitewash near the street, and you will find, as in this case, a monster midden pit, with privies at each end, open to the front of a whole row of houses whose inhabitants they serve. The clothes of the poor people are actually hanging to dry over this disgusting pit; and the pebble pavement around is befouled by the children in the yard, for whom no provision whatever has been made. Peelings, slops, tea-leaves, are strewn about the yard. This pit, of awful dimensions, receives the whole of the refuse from the various families in the row; which lies there rotting for weeks and months, and is then disturbed and carried through into the main street. We noted at the lowest point next Friarsgate a shutter up to indicate a death.

In Milling’s-yard [MELLING’S YARD], a little farther on, matters were a little better, as there were gratings at intervals through which liquid refuse passed away; but at each of these there were collections of solid filth around, which could not get through, and yet were not swept away.

The semi-circular apse end of ST. GEORGE’S CHURCH, full of richly-painted glass, is within a dozen feet of the poor homes in this yard: clothes-lines are tied to the church-yard railings, and a quantity of clothes hangs fluttering, like banners, over the graves. The church-yard is, properly, closed. The church is but a travestie of Norman work,—the tower-porch, something between a porch and a tower, being in marvellously bad taste.

There are plenty more yards on both sides of the road,—Tayler’s-yard [TAYLOR’S YARD], BROWN’S YARD, Cradwell’s-yard [GRADWELL’S YARD], with “lodgings for travellers:” and all the kennels are running with slops and mud. A space bounded by CHAPEL YARD is so cribbed and confined, that the rear premises of respectable shops and privies and ash-pits jostle each other in the smallest space that could by any stretch of imagination be called a yard; and over these the inhabitants have to hang their linen to dry.

A passage before coming to Union-street [LILL’S COURT] has a marine store and rag and bone shop at one end and a candlemaker’s at the other; and in UNION STREET flows a kennel full of moist filth, slops, and tea-leaves, which has a slow current into Friarsgate.

In the rear of SNOW HILL there is another similar neighbourhood [STARCH HOUSES?]: oyster-shells are strewn about, and the ground is the common privy for children. Pawnbrokers and marine-store dealers flourish around.

HIGH STREET is a row of poor houses, about one-eighth of a mile long, with small back yards and at the back of these a huge sewer positively discharges itself on to the surface, and forms a wide bog, the whole length of the row of houses. The solid filth from this overflows the outlets, and stops up the privies of the High-street residents; and to see an old woman raking in the filth to find the sewer was a pitiable spectacle. A man, standing by, remarked that it had been nearly as bad as that for nine years, to his knowledge “never anything but a bog, even in summer,” but that, since PEADER & LEVER had begun to boil tripe at the top of the street, and throw their boiling greasy water on to the sewage, it was daily getting worse. It must he observed that this is not a made ditch. The Board of Health —or, more correctly speaking, of Illness —has brought a sewer up to the high end of the street, and then discharged its contents, to make its own way. As the ground falls the sewage has made a course for itself; and the overflowings from aged pigsties, middens, and pits, belonging to the houses in High-street, have run into it in tributary streams!

The back windows of the houses overlook a large plot of ground in a transitory condition, known by tradition only, as the ORCHARD, which is partly built upon and partly used as a play-ground by the “roughs.” A spacious METHODIST FREE CHURCH AND FREE SCHOOLS are planted in the midst; while, in another part of it, A PERMANENT WOODEN CIRCUS has been set up, which looks like a vast conical tumulus, or an aboriginal’s hut. The rest of the Orchard is a surface of thick, black, hard mud, on which men are playing at “putting the stone” and “pitch and toss,” and on which a tribe of pigs are disporting pork fashion. Great holes are worn in this muddy play-ground, and pools of offensive colour and odour finish the landscape. There is another route to be taken.