See also: Nigel Morgan’s Social and Political Leadership in Preston 1820-60

1. Winckley Square: Setting the Style

Although its size cannot compare with Hyde Park, its beauty with St James Square, nor its lunchtime entertainment with Lincoln’s Inn Fields, the effect of Winckley Square is similar to those places. A mere hundred yards south of the bustle and rush of Fishergate, the Square suggests the tranquillity of the countryside. The visual reason for this nowadays is that trees obscure most of the buildings surrounding it. This historical reason is that before 1800 this was ‘Town End Field’.

It is astonishing to discover that the idea for a great square was conceived about 1800, when Preston was hardly more than an ambitious village, elegant citizens had to be carried over the mess of its unmade streets in sedan chairs, and ‘Town End Field’ was just part of the countryside between the town and the river.

The square was planned by Thomas Winckley and William Cross. Thomas Winckley, a member of an old and well-established local family, owned most of the land. William Cross, a prominent local lawyer who seems to have been the driving force behind the scheme, bought some of the site from Mr Winckley, and other parts (on the east side) from two Fishergate tradesmen (Butler and Woodcock), whose land extended in this direction from the yards named after them. This was in 1801.

William Cross had already built a house for himself on the north side, at the east corner of Winckley Street, with a garden beside it and a coach yard behind (now Preston College Annexe). He was immediately followed by one of the principal inhabitants of the town, Col. Nicholas Grimshaw (councillor, alderman, Town Clerk, and mayor several times over), who built on the opposite corner (No. 4, now solicitors’ offices). At the west end of this side, which was then known as Winckley Place, two other houses were built or soon occupied by equally prominent men, Edward Gorst and Richard Newsham, and in 1804 John Gorst built the first house of the half-formed square, and Mr Dalton of Thurnham Hall near Lancaster (then living in Preston) built another.

This laid the foundation of what was to become the most fashionable location in Preston and in 1805, to make sure that its continued development was in keeping with its beginning, William Cross had a binding legal agreement, or deed of covenant, drawn up to be signed by present and future purchasers of plots in the square: ‘Condition for executing a plan of Lands intended for building upon belonging to William Cross Esq. on the East Side of an intended Square in Preston’ (Lancashire Archives: DDPd11/59 and 60). This document shows that instead of imposing his own conditions for building and design, William Cross worked them out together with the other residents; and that he intended the collective management of the Square to continue in the future. ‘A majority of the proprietors’ were to have the power of laying out the interior ‘as a pleasure ground without Rent and to have Keys of the General Entrance Gates with Liberty to make Iron Gate Entrances opposite their own Houses.’ There were to be ‘Proprietors’ meetings’ every 15th April and 15th November at Mr Cross’s office ‘when a majority shall have powers to regulate the planting Walks Lighting and Cleansing of the Square’, paying for such management by a rate per yard on the frontage of each house.

In this way the residents of Winckley Square were to act as a single group. The conditions for building the houses (in the same document) make it very clear that they were to be a rich and exclusive group, and that the architecture of the houses should express these ideas:

The houses to be built three Stories High and to be uniform in the Front as near as may be. so as to correspond, in general Appearance, with the House built by the said John Gorst, and not to be of less annual value than Forty Pounds. (Article 9)

An ‘annual value’ of £40 (meaning the sum for which a house could be rented) was very high: four times as high as the fairly restrictive qualification for voting in boroughs introduced in 1832; and about eight times the value of an ordinary ‘terraced’ house.

Perhaps because Mr. Cross did not lay out the southern half of the Square until some years later, further development was rather slow. Myre’s map of 1836 shows that the scheme was still only about three-quarters complete thirty years after it was begun. (The map also gives a revealing picture of the fate of Mr. Cross’s ideal of a communal pleasure ground)

Whether complete or not, Winckley Square had a marked effect on the social geography of Preston. It acted like a powerful magnet, attracting into its vicinity almost everybody who was anybody, or who wished to be somebody. A good down-to-earth reason for this was that it helped to maintain a high value for property in the area; but there were also human and social reasons. It is not simply that people who could afford to be snobbish frequently were, but that, half a century before the introduction of telephones, it made sense to live close to other people who had information which might be important. Mill owners and magistrates, property owners and lawyers, merchants and bankers, made natural companions.

Geographically, the site was ideal. Not only was it south-west of the town centre, and therefore usually up-wind of all the reeking chimneys (multiplying from month to month), but the natural boundary of the river prevented any further industrial development in that direction.

2. Social Amenities of the Winckley Square Area

To these natural advantages, the residents of the area in the 1840s added social advantages, either as private citizens collaborating with one another in clubs and societies, or as members of the Corporation; which sometimes seems to have been much the same thing. It is hard to avoid the impression that what they were really doing was appropriating institutions which belonged to the town as a whole. These were the Grammar School, the Literary and Philosophical Institution, the Gentlemen’s Newsroom, and the Mechanics Institute (which in Preston called itself the Institution for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge): all removed into the Square or close to it from premises formerly located in Stoneygate, the Corn Exchange, the old Guildhall, and Cannon Street, respectively.

The first three were built on a site at the north corner of Winckley Square and Cross Street, in an interlinked scheme conceived in 1841. Traditionally the ancient Grammar School existed for the education of the sons of the freemen of the borough, and at this time it was located behind the headmaster’s house (Arkwright House) at the bottom of Stoneygate, and had 65 pupils. When the Corporation’s Grammar School Committee proposed that the school should be moved to ‘a more suitable building’, the Mayor suggested erecting ‘a building embracing different purposes, such as the Mechanics’ Institution, the Philosophical Society, the School, the Library, etc.’ Some councillors objected that the Grammar School, which ought to be for the benefit of the poor and the sons of mechanics and such like, would then become exclusive to the sons of gentlemen who could afford the fees. But this argument was defeated, the new school was built in Cross Street, the fees were raised, and in 1845 there were only two sons of the ‘poor freemen’ among its pupils.

The Literary and Philosophical Institution (or ‘Lit. and Phil’) was formed in 1810. The members had been meeting in the Corn Exchange Rooms in Lune Street to hear enlightening lectures on such topics as ‘the genius of Shakespeare’, ‘Italian Language and Literature’, and ‘The Anatomy and Physiology of the Eye’, but in 1845 it was likewise removed from the old town centre, to the ornate Gothic building facing the Square which it shared with the Winckley Club. This new club replaced another old institution which had been in the town centre, the Gentlemen’s Newsroom in the Guildhall. The club was composed of 100 shareholders including 24 mill owners, 22 lawyers. 7 bankers. and the proprietor of the Preston Chronicle (lsaac Wilcockson). Just what these gentlemen got up to in it at that time may never be known (apart from its newspapers and journals it probably provided a respectable alternative to the bar of the Bull Hotel), but one thing is certain: as a newsroom it was no longer open to other gentlemen of the town. Membership was by shareholding, the number of shares was fixed, and they were transferred from father to son by will, or occasionally sold, just like any other form of real property.

As these buildings were being completed, the Institution for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (or Mechanics’ Institute) was hijacked from its premises in Cannon Street (now the Bodega Bar, and recently reduced after a fire). It had been established in 1828 to encourage self-help adult education for all classes, but especially working men, with the ideal of ‘perfect equality’, and by 1835 its 300 members included 44 mechanics, 40 labourers and porters. 20 shoemakers, 24 tailors, and so on. For quarterly subscriptions of one shilling and seven pence (roughly equivalent to half a week’s rent) they could use the library, learn English grammar or French, take classes in vocational skills such as architectural drawing and book-keeping; and attend the programme of lectures, which was as varied as those of the Lit. and Phil. but more practical (elocution and phrenology were popular, and so was an evening on the new science of electro-magnetism). Unfortunately ‘perfect equality did not last very long, and by the early 1840s working men were a minority among bankers, professional men and ‘gentlemen’. The new membership, encouraged by the Corporation, then acquired a new site at the top of Ribblesdale Place. As one of the founder members, Joseph Livesey pointed out in the newspaper which he had just started:

If the building be intended as an ornament to a part of the town that needs it the least . . . nobody ought to complain except perhaps, those members who are attached to Cannon Street … [But] a more unlikely site could scarcely have been chosen. It is quite at an outside corner of the town, and convenient only to the comparatively wealthy. And not only so, but it will become less and less central as the town extends. (Preston Guardian 31 Jan. 1846)

He might have said the same about the Corporation’s plans for a public park, on lands which it had just acquired on the bank of the river below Ribblesdale Place. This purchase, of what is now Avenham Park, had been recommended by the Mayor (John Addison) with such breath-taking hypocrisy that it must have been unconscious:

With respect . . . to the particular classes whose advantage was chiefly contemplated . . . they must recollect that they are those who have little leisure, except during certain hours of the day . . . this made it the more necessary to provide for them near their homes. (Preston Chronicle 31 Aug. 1844)

The Cross Street buildings having been demolished and replaced with modern offices, only the Avenham Institute and the Park are left as architectural evidence of the way the new middle classes of early Victorian Preston feathered their own nests in this area. They had provided for the formal education of boys, the informal education of adults, the indoor recreation of men, and the outdoor recreation of all, on their own doorsteps. All except the park had been removed from locations where they had been more convenient for the rest of the population, but which had perhaps had the uncomfortable disadvantage of exposing fashionable folk to the mockery of their inferiors as they passed among them. The one thing lacking was an estate church, but sectarian rivalries in a town with so many Catholics and Nonconformists would have caused disagreements. The residents might hold different beliefs on a Sunday, but when it came to social values in the rest of the week, they were as one

3. Houses and Households of the Stylish . . .

The houses in Winckley Square are large and originally they were almost all detached. Later additions in gaps and gardens between them give the impression that they were built in rows or terraces, especially on the north and west sides, but vertical joints in the brickwork shows that this was generally not the ease (e.g. at the north end, joints to the left of No 4 mark the edges of a plot which was still vacant in 1840: see Fig. 2 above). As far as it is possible to tell nowadays, all these large houses on the north, east, and west sides had full service basements, those on the east and west sides opening directly onto the sloping yards and gardens behind (some of which probably contained stables and coach houses as well). The substantial villas built on the south side in the 1830s and 1840s, and the row in the south west comer, have large cellars; but because the level of the ground was unsuited to basement kitchens, sculleries and so on, they have rear service wings for those rooms; and one or two had stables and coach houses as well (for example, No. 15. where the coach house is still recognisable in Back Starkie Street).

Built ‘double fronted’ (i.e. with the front door in the centre, or close to it), all these houses have (or had) wide entrance hallways lit by fanlights, with drawing and dining rooms on each side, and generous and elegant staircases ascending from the far end. They are almost all three storeys high, and some also have attics, the top floor providing servants’ rooms. The house which Thomas Miller added in 1854, No. 5 in the north-east corner, has two staircases built parallel and separated by a wall, the back stairs being for servants so that their comings and goings could be segregated from the family; and one or two of the houses on the south side of the square also had servants’ staircases until recently.

Apart from Ainsworth’s stone ‘Italian Villa’ (built about 1850 on the corner of Cross Street, but demolished in the 1960s) and Miller’s of 1854 in the north east corner, the houses were designed in the restrained classical style typical of the late Georgian period, with little decoration except for their doorways

Seen from outside, only the size of these houses, and the ‘iron pallisadoes’ (or railings) to their basement ‘areas’ suggest the nature of their households, but the census returns reveal that in 1851 the families living in the square had an average of one servant to each person: 66 family members and 64 servants in all.

The residents in 1851 (according to the Census of that year)included seven mill owners who between them employed about five thousand people, a third of all the mill-hands in the town. Thomas Miller (then living at No. 3), in charge of Horrocks Miller & Co., employed 2,000; John Swainson (No. 6) and William Birley (No. 7) employed another 1,400; Thomas and William Ainsworth (No. 10) 800 at Church Street mills, and Paul Catterall (No. 14) 750 at Park Lane Mill. Other busy residents were lawyers, such as Joseph Bray (No. 4). John Gorst (No. 5). Peter Catterall (No 15). and the brothers John and Thomas Batty Addison just off the north side at No. 7 Winckley Street; or physicians and surgeons who be mostly lived on the south and west sides. The rest were either bankers, or people who did not need to work at all, such as Richard Newsham at No. 1, who described himself as ‘landed proprietor and fundholder’

None had fewer than two servants, most had three or four. Although most of the servants were probably maids of all work, a few were not maids at all: Joseph Bray’s staff included a ‘manservant’, John Addison’s a ‘coachman’; and two others had ‘grooms’. Some of the female servants were specialists, such as William Birley’s ‘housekeeper’, and John Addison’s ‘cook’. Peter Catterall’s staff of four included a ‘cook’ and a ‘female waiter’, and Thomas Miller had two ‘nurses’ for his two small children. The most highly organised staff was kept by Thomas Ashton, a magistrate living on the corner of Starkie Street, whose young wife and two small boys were served by a maid, a housemaid, a cook, a needlewoman, and a groom. (And the occupant of No. 11 Starkie Street nearby was a ‘dancing master’)

4. . . . and the Comfortable

Following the trail of luxury out of Winckley Square brings us, with a slight but immediate drop, into Ribblesdale Place, and thence to Bushell Place and Bank Parade; Camden Place and Starkie Street linking the Square with Ribblesdale Place and slightly inferior to it

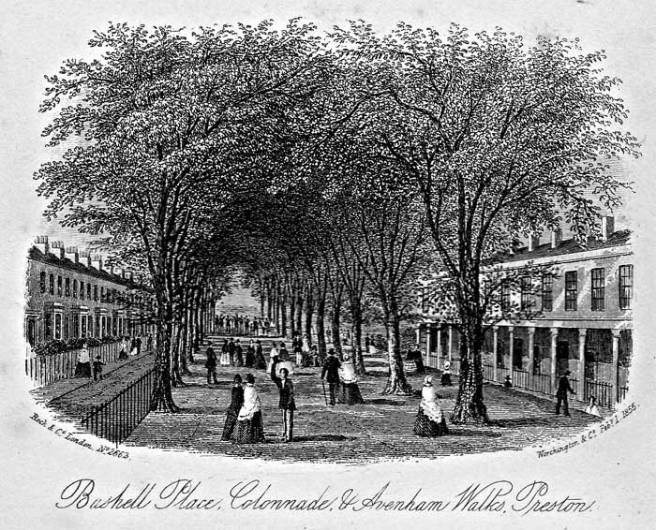

The choice side of Ribblesdale Place was the south, where the first houses were built in the 1820s and 1830s, their service basements exploiting the slope overlooking the river. Two or three were detached villas; but most were semi-detached, and those at the east end, facing Avenham Walk, were built as a colonnaded row (Avenham Colonnade – now lacking this identifying feature). These houses had large service basements, opening into the gardens behind, and the numbers of resident servants – mostly two or three – were correspondingly higher than on the other side of the road. Some still have beautiful examples of basement ‘area’ railings, with gates. The houses on the opposite side were not built until the 1840s, mostly in short terraces, and they were lower in value (the deeds of No. 34 dictate that it should let for at least £14), but they had service cellars, and most had one or two resident servants. (Some of the houses in Ribblesdale Place appear to have been rebuilt or remodelled in the 1890s).

Bushell Place was built on land belonging to the trustees of Bushell’s Hospital in Goosnargh, beginning about 1830 (when only six houses are recorded in the Land Tax book, and four were still empty). Here, the form of the houses was arranged so as to get maximum value from this choice but limited site. They are large but appear small from outside because they were built as a uniform 2-storey row on long narrow plots, so that each house is only single-fronted; but the best plots allowed for rear wings which were exceptionally long, and the houses have capacious cellars as well. In 1851 the 15 houses in Bushell Place were staffed by a total of 29 resident servants.

We come to the end of this social line round the comer in Bank Parade; but nobody following this route on foot should fail to turn it, because Bank Parade is an extraordinary and delightful monument to Victorian individualism, the architectural opposite to the uniformity of Bushell Place. Built at different dates (from about 1840), by different people and in different styles, it finished up as a row: one can almost visualise the purchasers of the plots jostling one another for a place where their sewage could run so conveniently into the river. Among the few features which they have in common are large cellars, connected by tunnels under the road to gardens on the slope below. In 1851 there were 13 houses in Bank Parade and 24 resident servants: two per house, which is the same ratio as Bushell Place

The social composition of the residents of Ribblesdale Place, Bushell Place and Bank Parade, was roughly similar: compared with Winckley Square, there were no medical men, far fewer bankers or lawyers, and relatively fewer mill owners and manufacturers. Instead, merchants and specialised shopkeepers make their appearance: for example, wine merchants and corn merchants in Ribblesdale Place and Bushell Place, a tea dealer in Bank Parade; a tailor and draper, and a grocer in Ribblesdale Place; a pawnbroker, a leather dealer and a woollen draper in Bank Parade. Isaac Wilcockson, ‘retired printer’ and proprietor of the Preston Chronicle, lived at 12 Ribblesdale Place. J .J. Myres, ‘Land Surveyor’ who managed much of the building of workers’ houses (see Deadly Dwellings) at 9 Bank Parade; and, further along in this row, two officials of central government were next door neighbours: William Kennedy, Inspector of Schools, and Joseph Ewings, Factory Inspector. There were three Church of England clergy: Robert Harris, curate of the fashionable St. George’s chapel, at 13 Ribblesdale Place, and the curates of the parish church and of Trinity church in Bushell Place; and one teacher: the Master of the Grammar School at No. 1 Ribblesdale Place. The largest group of all were those who had independent incomes; three ladies in Ribblesdale Place and one in Bushell Place who were ‘proprietors of houses’, and another in Bushell Place whose occupation was ‘Railway shareholder’; a couple of ‘retired builders’, an ‘annuitant’ in Bank Parade; and several others who described themselves less helpfully as ‘gentlemen’.

Although the general impression of the inhabitants, as of the houses, is that they were not quite ‘la crème de la crème‘, some of the leading councillors and cotton employers were not too proud to live among them. John Catterall, mill owner and mayor, lived at 14. Bushell Place; an alderman and former mayor, the elderly John Paley, at 14 Ribblesdale Place, and at No. 3 a junior member of the Horrocks family, John Horrocks, partner of George Jacson in Avenham Street mill. The back of John Horrocks’ house overlooking the park, bears a striking similarity to Lark Hill and the interior still has original moulded plaster decorations (the richest I have seen in any house in Preston)

Among the resident servants, as in Winckley Square, there were a minority of specialists, mostly housekeepers, cooks, and nursemaids, but at No. 19 Ribblesdale Place there was a ‘footman’. and at No. 16 a ‘groom’, The largest staff was in mayor John Catterall’s home at 14 Bushell Place: a governess, a cook, a nurse, and three other servants. The most down-to-earth was that of the Quaker leather merchant, Michael Satterthwaite, who had a ‘washerwoman’ at No. 10 Bank Parade. And the most interesting was at No. 5 Bushell Place, where Anthony Belcano (‘foreign merchant) described his wife as ‘pudding maker to the family’ – or was this her own comment?

This, then was ‘the Downing Street of Preston’ in 1851, the domestic centre of government (such as it was), and of the management of cotton mills, law, money and land. Its richer and more powerful residents did not light lamps or fires, they did not cook, they did no washing or ironing, nor did they empty chamber pots; they certainly never fetched water or cleaned earth closets (see below); and perhaps they never saw these things done and did not know how to do them themselves. This is what makes them different from the merely respectable inhabitants of the rest of this area.

4. Middle Class Housing Elsewhere

The concentration of fashionable society in and around Winckley Square in the first half of the 19th century was so marked that comparable houses elsewhere in the town were few and far between. A terrace here, a few villas there, remained as small islands in the later sea of mills and workers’ housing. Nevertheless, this chapter would be incomplete without any mention of Moor Park, West Cliff, Wellington Terrace or Stephenson Terrace.

What is now Moor Park, a long rectangle tree-fringed grassland lying between Garstang Road and Deepdale about a mile north of the town centre, was formed by the Corporation in 1833-6. The Corporation’s motive at that time was not the generous and enlightened one which posterity has since attributed to it: it was inspired, not by a desire to provide the town’s overworked factory/hands with a place of innocent recreation on Sundays, but by a desire to raise money by selling the rest of Preston Moor as building land. The snag was that the 240-acre Moor was ancient common-land, where all the freemen of the borough had rights of pasturage for their pigs and cattle. The Corporation therefore decided to buy off the freemen’s opposition to enclosure by reserving about 100 acres as permanent meadow, with a Serpentine Road on the north side and a straight road on the south side, bounded by a ‘ha-ha’ to keep the animals in and allow promenading spectators a good view. As it happened, the townsfolk of industrial Preston had little interest in keeping cattle, and for most of the next thirty years the intended ‘pasture’ was let annually to a certain Matthew Brown, brewer, who grew barley on it. It was not made into a park until the 1860s when mill workers put out of work by the Cotton Famine were provided with employment such as road making and ‘landscape gardening’ (on a rather large scale).

Nevertheless. the guarantee of an open vista in this area made that portion of Garstang Road an attractive site for building superior villas, and by about 1850 there was one on the east side to the south of the park and another three or four on the west side, facing it, all going by the address ‘Moor Park’.

What is specially interesting about them is that three were occupied by mill owners whose mills were situated alongside the Moor Brook, which then formed an approximate boundary to the built-up area of the town: Richard Threlfall (Broomfield Mill), John Goodair (Brookfield Mill) and George Smith (Moorbrook Mill). All three were councillors for this ward (St Peter’s), and Goodair and Smith were not only friends but also leading lights in the minority but rapidly rising Liberal party of Preston. None of these men identified themselves with the Tory grandees of Winckley Square, but their domestic lives appear to have been at least ‘comfortable’ (by my definition), because Richard Threlfall had three resident servants (housemaid, nurse and cook), and the others had two each, John Goodair’s ‘Italian Villa’ still stands [no longer], but George Smith’s Beech Grove was recently demolished (the stone taken away and re-erected as an exclusive mansion at Alderley Edge in Cheshire).

Were it not for the North Union railway (under construction in the late 1830s), it is likely that the spread of superior housing round Winckley Square would have been westwards, in the area now covered by the railway station and its associated yards, and then down the south side of Fishergate Hill. The Tithe map of 1840 shows the beginnings of several intended streets in this area, but with the line of the railway separating them from Winckley Square. All that remained of the earlier development were a few groups of houses on Fishergate Hill, two short terraces leading off the north side (Spring Bank and Stanley Terrace), and West Cliff running off the south side.

West Cliff itself, following the crest of the western bluff overlooking the river, was obviously planned so that houses on that side could be provided with full service basements built into the slope, rather than laboriously excavated. In 1840 there was one, and by 185l there were seven large detached villas here, five occupied by prominent members of the legal profession and two by mill owners, looked after by the largest domestic staffs in the town. At No. 2 the elderly William Winstanley and his various relations had seven servants to cook, light fires, clean, and wash for them. On the opposite side of the road West Cliff Terrace was begun about 1851, a fine example of terraced town housing for the middle classes, which would not be out of place in Bloomsbury: its external appearance suggests that the principal rooms were at first floor. That was all; but it is enough to suggest what might have been if the railway had taken a different route.

Like West Cliff Terrace, both Wellington Terrace and Stephenson Terrace were still being built in 1850-51.

Wellington Terrace is another example of housing built at the top of the slope above the Ribble valley, to provide for service basements; but, unlike Ribblesdale Place and Bank Parade, with all the advantages of proximity to fashionable society in Winckley Square, it was quite unfashionably located at the north-west corner of town, and uncomfortably close to the Blackpool railway line. Only four houses in the terrace were completed by 1851, and they were occupied by men whose families could afford only one resident servant each: a commission agent, a machine maker and worsted spinner who had a small steam mill in Fylde Road nearby; a cotton ‘manufacturer’ (i.e. an employer of handloom weavers) whose business was then based in Mount Street but who soon acquired a mill beside the canal north of Aqueduct Street; and a ‘master bricklayer’ employing 20 men who had just moved out of St Paul’s Square.

Stephenson Terrace is at the opposite (eastern) end of the town. Here, at the south end of Deepdale Road, a small vestige of Preston Moor was left as a triangular green (which once had its own lodge, and may have resembled the communal garden of Winckley Square). The Longridge railway passes a short way to the north, and it may have been the ambitions for this line – built in the mid-1840s by the Fleetwood, Preston and West Riding Railway Company – which encouraged Mr George Mould to build a very ambitious-looking terrace on the east side of the green.

Stephenson Terrace is at the opposite (eastern) end of the town. Here, at the south end of Deepdale Road, a small vestige of Preston Moor was left as a triangular green (which once had its own lodge, and may have resembled the communal garden of Winckley Square). The Longridge railway passes a short way to the north, and it may have been the ambitions for this line – built in the mid-1840s by the Fleetwood, Preston and West Riding Railway Company – which encouraged Mr George Mould to build a very ambitious-looking terrace on the east side of the green.

Stephenson Terrace (named after a member of Mr Mould’s family, not the famous engineer) is Preston’s only true terrace, designed like an 18th century mansion, as a single composition: mostly two-storeyed, but with an eight-bay centre and four-bay flanking wings of three storeys. It was given added distinction by the use of sandstone for the façade, emphatic Tuscan porches and chunky bay windows at ground floor, raised front gardens (formerly surrounded by iron railings), and a back service road. The impression of grandeur successfully disguises the fact that the houses themselves were quite ordinary: only their individual rear extensions (making yards of amazing meanness between them), and their cellars and attics, distinguish them from standard three-room plan houses. Those houses in the terrace which I have examined have two cellar rooms; and in one of these the front cellar is fully equipped with a primitive cooking range, a washing boiler and a slop-stone. This cellar must have been staffed by more than one servant, and the arrangement of the large attic, with its own staircase disguised as a cupboard, shows where the servants were accommodated (See Chapter Five below.) All the houses in Stephenson Terrace had such cellars and servants’ attics, despite the apparent difference between two and three storeys – which is an architectural illusion contrived by lighting the attics of the two-storey houses through sky lights in the roof.

Only about half the 24 houses in the Terrace had been completed by 1851, and they were mostly occupied by families of four people with either one or two resident servants. The heads of the households included three of the lesser cotton spinners and manufacturers, two army officers, an architect, a civil engineer, a corn merchant, and the vicar of All Saints Church – which had just been built especially for his flock of devoted ‘working men’.

Stephenson Terrace belongs to the Comfortable level of Preston’s middle classes, while pretending to be something more. Barton Terrace, which stands next to it just to the south, has no such pretensions. This row of eighteen houses built in the early 1830s with front gardens and small two-storey back extensions, but only a few with cellars, was occupied in 1851 by clerks, managers, journeymen-craftsmen, a shoemaker, a straw bonnet maker, and such like, only four of whom had living-in servants.

The residents of both these terraces must have known one another by sight, but were the children of Stephenson Terrace permitted to play with the children of Barton Terrace? The juxtaposition of Barton Terrace and Stephenson Terrace in Deepdale is perhaps the neatest visible demonstration in Preston of one of the sharply defined steps in the scale of local society in the middle of the last century. The next chapter explores the more constricted world of mere Respectability.